Politicians’ Corruption is People-Driven – Sen. Ndume

By Bala Salihu Dawakin Kudu

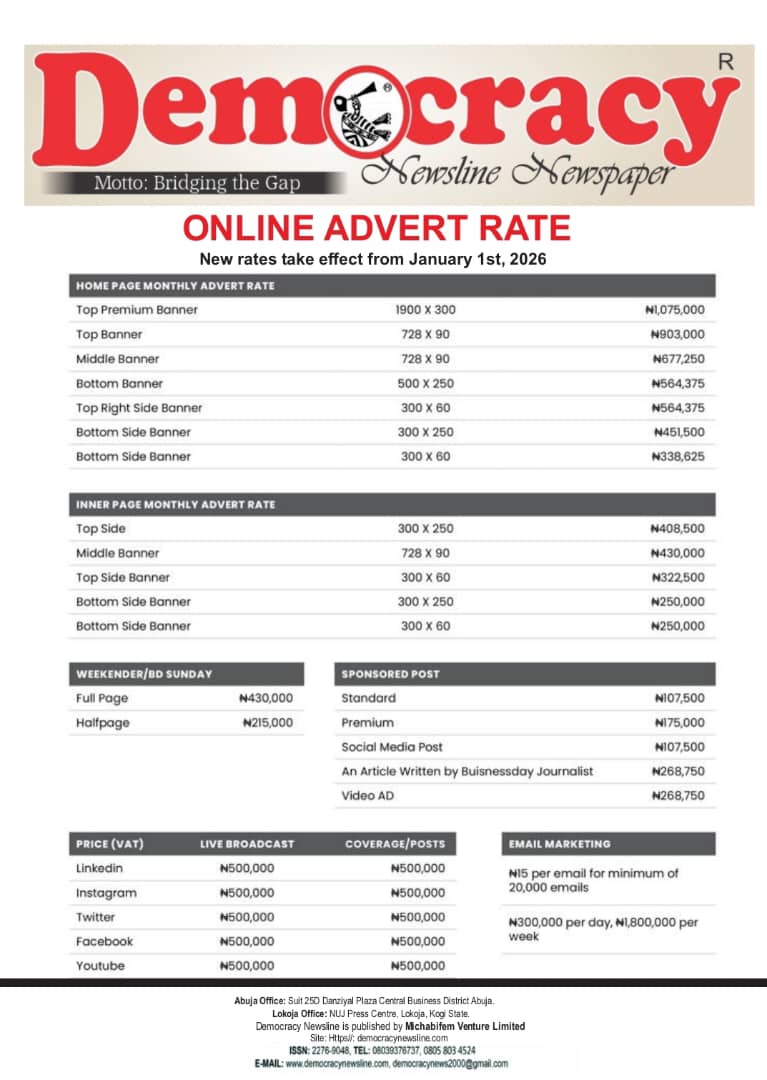

Democracy Newsline

February 20, 2026.

In a nation long burdened by the weight of corruption scandals and unfulfilled promises, a startling confession has ignited fresh debate across Nigeria’s political landscape. Senator Ali Ndume has declared that corruption among politicians is not merely a product of personal greed or institutional decay, but is, in his words, “people-driven.”

The outspoken lawmaker, who represents Borno South Senatorial District in the National Assembly of Nigeria, made the assertion during a recent interaction with journalists, sending shockwaves through the polity.

According to Ndume, many elected officials feel compelled to siphon public funds to satisfy relentless demands from constituents who expect financial handouts as dividends of democracy.

“Let’s be honest,” he reportedly said. “No politician in the National Assembly can stand up and claim to be completely clean. Some steal and share with the people. Some steal and keep it to themselves.”

Nigeria’s democracy — a system where patronage often overshadows performance, and immediate financial gratification trumps long-term development. In many communities, politicians are expected to provide direct financial assistance for weddings, funerals, school fees, hospital bills, and even daily subsistence.

Political analysts say this entrenched culture of dependency has blurred the lines between public service and personal largesse. Instead of holding leaders accountable for policy implementation, infrastructure, and legislative performance, some constituents prioritize who brings “something home.”

Dr. Amina Yusuf, a political sociologist at the University of Abuja, explained that this phenomenon is rooted in poverty and institutional failure.

“When citizens lack access to basic services, they turn to elected officials as alternative providers,” she said. “It creates a cycle where politicians divert public funds to meet personal requests, reinforcing corruption as a survival mechanism.”

Nigeria’s anti-corruption agencies, including the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC), have long battled graft within public institutions. High-profile convictions and ongoing investigations have done little to erase public perception that corruption remains endemic.

Transparency International consistently ranks Nigeria among countries struggling with corruption challenges. Critics argue that beyond enforcement, the country must confront the social norms that normalize bribery, vote-buying, and the monetization of political loyalty.

Ndume’s assertion that “no one is clean” within the legislature may be hyperbolic, but it reflects a widespread belief that systemic corruption transcends party lines. The statement has drawn mixed reactions, with some praising his candor and others condemning it as an attempt to deflect responsibility.

Civil society groups have expressed outrage, insisting that shifting blame to citizens risks excusing criminal behavior. “Corruption is a crime, regardless of public expectations,” said a spokesperson for the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre. “Leadership requires integrity and the courage to say no.”

On social media, Nigerians have engaged in heated debates. Some argue that voters who accept cash during elections inadvertently empower corrupt officials seeking to recoup their “investments.” Others counter that impoverished citizens cannot be blamed for accepting temporary relief in a struggling economy.

Political commentator Ibrahim Sani believes Ndume’s comments, though controversial, open a necessary conversation. “He is touching on an uncomfortable truth,” Sani noted. “But acknowledging societal complicity does not absolve those who take the oath of office from accountability.”

Experts suggest that breaking the cycle requires multifaceted reform: strengthening institutions, improving public sector transparency, promoting civic education, and reducing poverty. Electoral reforms to curb vote-buying and stricter campaign finance regulations are also seen as critical.

Furthermore, fostering a shift from transactional politics to issue-based engagement may help redefine the social contract between leaders and citizens. Communities must demand quality representation, effective policymaking, and measurable development outcomes instead of short-term handouts.

Ndume’s remarks serve as both a provocation and a mirror — reflecting uncomfortable realities about governance and civic responsibility. Whether his statement leads to introspection or mere controversy remains to be seen.

corruption in Nigeria is not a one-dimensional problem. It is woven into the fabric of political culture, economic hardship, and societal expectations. Confronting it will require not only honest leaders but also vigilant citizens willing to reject complicity.

The debate sparked by Senator Ndume may yet prove to be a turning point — if it inspires the nation to look beyond blame and toward collective reform.

(DEMOCRACY NEWSLINE NEWSPAPER, FEBRUARY 20TH 2026)