From Plan to Reality: Why Extending Social Protection to Nigeria’s Informal Workers Is Still So Hard

By Segun Tekun

A former International Labour Organization (ILO) Social Protection expert, Segun Tekun, has warned that Nigeria’s plan to extend social protection to more than 60 million informal sector workers may fail unless the country urgently confronts the deep structural weaknesses embedded in its social protection system.

In a statement issued on Monday, December 8, 2025; Tekun said that while Nigeria has progressive social protection laws, they remain largely ineffective for the informal economy, where over 80 percent of Nigerians work.

“Nigeria’s social protection system was built for offices and factories,” he said. “But Nigeria’s economy runs in markets, on farms, in motor parks, along coastal waters and across informal trade corridors,” he further said.

A National Problem Cutting Across All Regions

According to Tekun, the failure to extend social protection is visible across every region of the country.

In the South-West, market women in Ibadan and Abeokuta still pay out-of-pocket for healthcare despite the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act making health insurance mandatory. In Aba, dispatch riders and informal transport workers injured on the road rarely receive compensation under the Employees’ Compensation Act.

In the South-East, traders in Onitsha and Aba, despite running thriving commercial hubs, remain excluded from pensions and injury insurance. Across the North-West and North-East, smallholder farmers, herders and agro-pastoralists face droughts, insecurity and health shocks with almost no formal social protection support.

In the North-Central, artisanal miners and rural farmers experience frequent work-related injuries but lack access to compensation schemes. Along the South-South coast, fisherfolk lose livelihoods to flooding and oil pollution but have no structured insurance, health or income protection.

Health Insurance: Universal in Law, Selective in Practice

Tekun pointed to the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act 2022, which legally mandates health insurance coverage for all Nigerians, including informal workers, farmers and the self-employed. “Three years after the Act, universal coverage exists more in law than in real life,” he said.

He noted that State health insurance schemes in Lagos, Anambra and Kano still cater largely to civil servants and formal private-sector employees, while rural farmers and traders remain largely uncovered. “In rural communities in Jigawa or Benue, farmers sell produce to pay medical bills. In riverine areas of Bayelsa, fisherfolk still rely on traditional care or debt,” he explained.

According to him, fixed premiums, weak outreach and poor service quality continue to discourage informal workers from enrolling.

Workplace Injury: Invisible Risks in the Informal Economy

Tekun criticised the weak application of the Employees’ Compensation Act (2010), saying it rarely reaches workers outside registered companies. “A bricklayer injured on a site in Ilorin or a farmer injured by equipment in Kebbi bears the cost alone,” he said. He added that; small-scale farmers frequently experience injuries from farm tools, agrochemicals and machinery, yet remain completely excluded from compensation mechanisms.

“The law protects employers who register, not workers who suffer injuries,” Tekun stated.

Pensions: The Ageing Crisis Waiting to Happen

Tekun further expressed concern over the implementation of the Pension Reform Act 2014, which established the Micro-Pension Plan for informal workers. “In practice, micro-pensions have barely reached traders, farmers or artisans,” he noted. “Across Katsina, Osun, Enugu and Cross River, informal workers see old age coming with fear, not security.”

He warned that without pension inclusion, Nigeria faces a future surge in elderly poverty, especially in rural and agrarian communities where family support systems are already under strain.

A System Built for a Formal Economy That Barely Exists

Tekun argued that the common thread across Nigeria’s health insurance, compensation and pension laws is a heavy reliance on formal employment structures, despite informal workers accounting for the majority of the labour force.

“Our laws mention informal workers, but the machinery still runs on deductions, registrations and enforcement mechanisms designed for offices and factories,” he said.

He warned that the Federal Government’s pledge to reach 60 million informal workers will fail unless social protection delivery is radically simplified and adequately financed.

What Must Change Now

Tekun called on Government to move beyond announcements and take practical steps, including:

• Using associations as entry points, by enrolling workers through market unions, transport groups, cooperatives and digital platforms.

• Subsidizing health insurance and pensions for the poorest informal workers instead of relying solely on contributions.

• Creating a single access point for health, injury compensation and pensions to reduce complexity.

• Amending regulations to clearly accommodate self-employed workers under existing laws.

• Publishing transparent coverage data, showing how many informal workers are actually benefiting.

Segun Tekun is a social protection expert with over a decade of experience supporting social protection reforms across Africa. He has worked on policy and programme design in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Liberia and Somalia, and previously served with the International Labour Organization (ILO) and UNICEF.

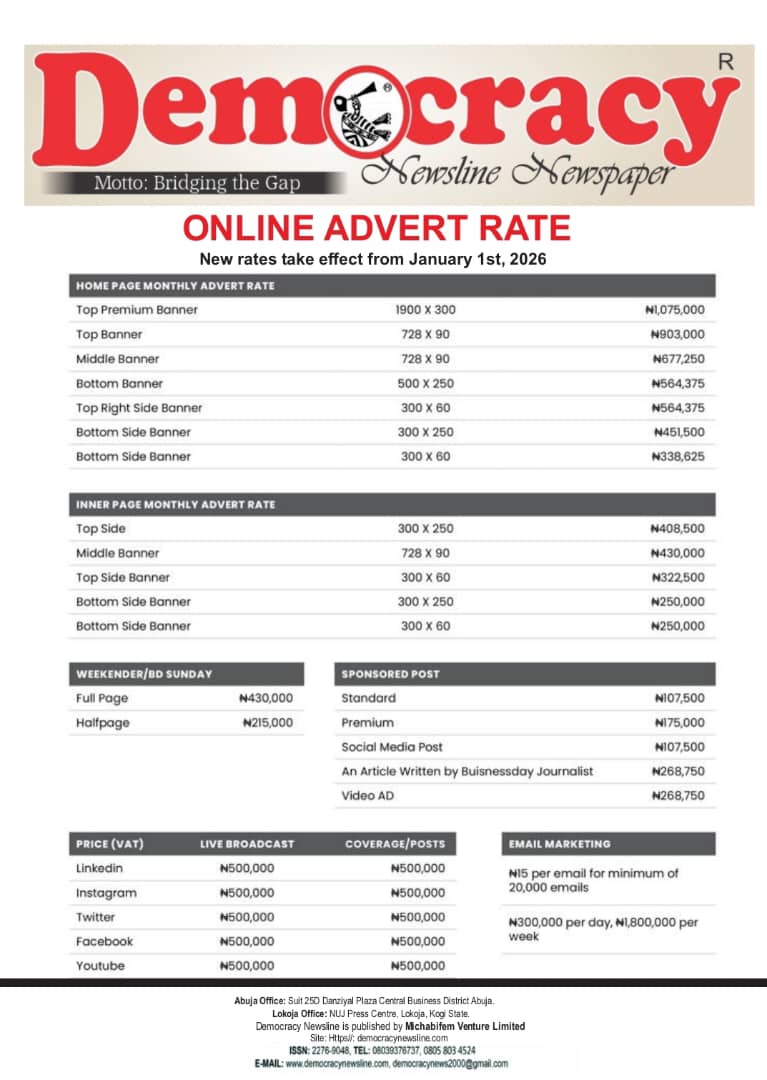

(Democracy Newsline Newspaper, December 11th 2025)