Malami Challenges EFCC, Asks Court to Set Aside Interim Forfeiture Order on Properties.

By Bala Salihu Dawakin Kudu

Democracy Newsline

January 2, 2026.

Former Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami, SAN, has taken a bold legal step against the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), asking the Federal High Court in Abuja to vacate an interim forfeiture order placed on some of his properties.

The development marks a fresh escalation in the growing legal battle between the former justice minister and Nigeria’s foremost anti-corruption agency, a contest that now raises fundamental questions about due process, asset recovery, constitutional rights, and the limits of ex parte proceedings.

Malami’s application specifically targets three out of the 57 properties earlier listed by the EFCC for interim forfeiture to the Federal Government. The properties—listed as No. 9, No. 18, and No. 48 in the EFCC’s schedule—are located in Kano and Abuja.

They include:

Plot 157, Lamido Crescent, Nasarawa GRA, Kano, acquired on July 31, 2019;

A bedroom duplex with boys’ quarters at No. 12, Yalinga Street, off Adetokunbo Ademola Crescent, Wuse II, Abuja, reportedly purchased for ₦150 million in October 2018; and

The ADC Kadi Malami Foundation Building, valued at ₦56 million, which Malami says is held in trust for the estate of his late father, Kadi Malami Nassarawa.

On January 6, 2026, Justice Emeka Nwite of the Federal High Court, sitting as a vacation judge, granted the EFCC’s ex parte motion seeking temporary forfeiture of the 57 properties, which the commission claims are proceeds of unlawful activities allegedly linked to Malami.

The judge also directed the EFCC to publish the interim order in a national newspaper, giving interested parties 14 days to show cause why the assets should not be permanently forfeited.

The properties—spread across Abuja, Kano, Kebbi, and Kaduna States—are estimated to be worth hundreds of billions of naira, fueling public debate and political reactions nationwide.

In a motion on notice dated January 26 and filed January 27, Malami, through a legal team led by Joseph Daudu, SAN, accused the EFCC of obtaining the interim order through suppression of material facts, misrepresentation, and exaggerated valuation of assets.

The application, marked FHC/ABJ/CS/20/2026, seeks:

An order setting aside the interim forfeiture on the three properties, which Malami insists were lawfully acquired and duly declared in his asset declaration forms submitted to the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB) in 2019 and 2023; and

An injunction restraining the EFCC from interfering with his ownership and possession of the properties.

According to Malami, the forfeiture proceedings amount to an assault on his constitutional rights, including his right to property, presumption of innocence, and family life.

Asset Declaration and Source of Wealth

Daudu argued that the EFCC failed to establish any prima facie link between the disputed properties and a specific criminal offence. He emphasized that Malami had openly declared his assets and income sources, which include:

1. ₦374.6 million from salaries, allowances, and official emoluments;

2. ₦574 million from disposed assets;

3. Over ₦10 billion in business turnover;

4. ₦2.52 billion in loans to businesses;

5. ₦958 million received as traditional gifts from personal friends; and

6. ₦509.88 million generated from the public launch of his book, “Contemporary Issues on Nigerian Law and Practice: My Travails and Triumphs.”

“These declarations constitute prima facie evidence of legitimacy,” Daudu submitted, insisting that the EFCC’s action was speculative and punitive rather than investigative.

The unfolding case exposes several critical challenges facing Nigeria’s justice system:

Ex Parte Orders vs. Fair Hearing.

The reliance on ex parte forfeiture orders continues to generate controversy, especially when high-profile individuals claim they were not given the opportunity to be heard before their assets were seized.

While asset recovery is central to Nigeria’s anti-corruption drive, critics argue that aggressive enforcement without clear proof risks undermining public confidence and constitutional safeguards.

Valuation and Transparency

Malami’s allegation of inflated asset values highlights the challenge of ensuring transparency and professional standards in property valuation used in forfeiture cases.

Political Undertones

Given Malami’s role as a former top official in the Buhari administration, the case has inevitably attracted political interpretations, further complicating public perception of the EFCC’s motives.

On January 27, the matter could not proceed as scheduled because it was not listed on the court’s cause list. The case file was returned to the Chief Judge for reassignment after Justice Nwite concluded vacation sittings.

Meanwhile, multiple lawyers were reportedly present in court, having filed applications on behalf of interested parties seeking to halt the final forfeiture process. As Malami also faces separate money laundering charges and is currently in DSS custody over allegations bordering on terrorism financing, the stakes remain extraordinarily high—for both the former AGF and the EFCC.

Beyond Malami’s personal fate, the case is shaping up to be a defining legal test for Nigeria’s anti-corruption framework: one that will determine how far the state can go in seizing assets, and how firmly the courts will insist on balancing enforcement with constitutional rights.

As the judiciary prepares to take a closer look at the competing claims, Nigerians will be watching closely—because the outcome may well set a precedent for future asset forfeiture cases in the country.

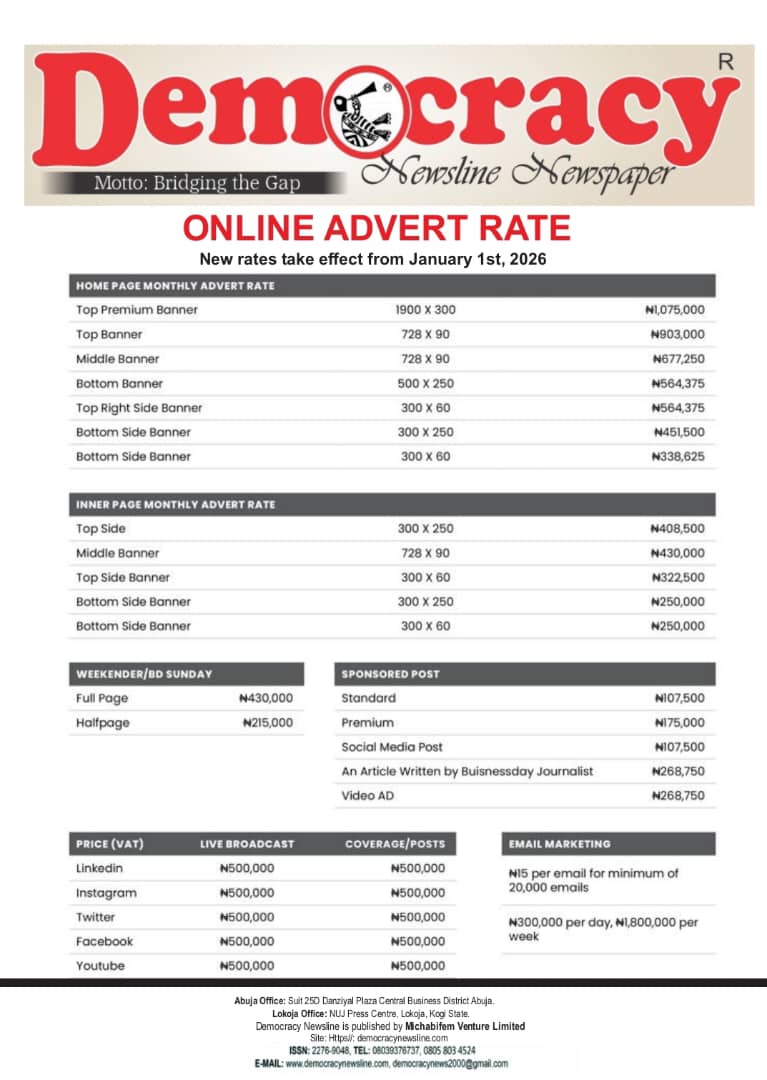

(DEMOCRACY NEWSLINE NEWSPAPER, FEBRUARY 2ND 2026)