Resign Now, Kano Deputy Governor Told as Loyalty, Constitution, and Power Struggle Collide.

By Bala Salihu Dawakin Kudu

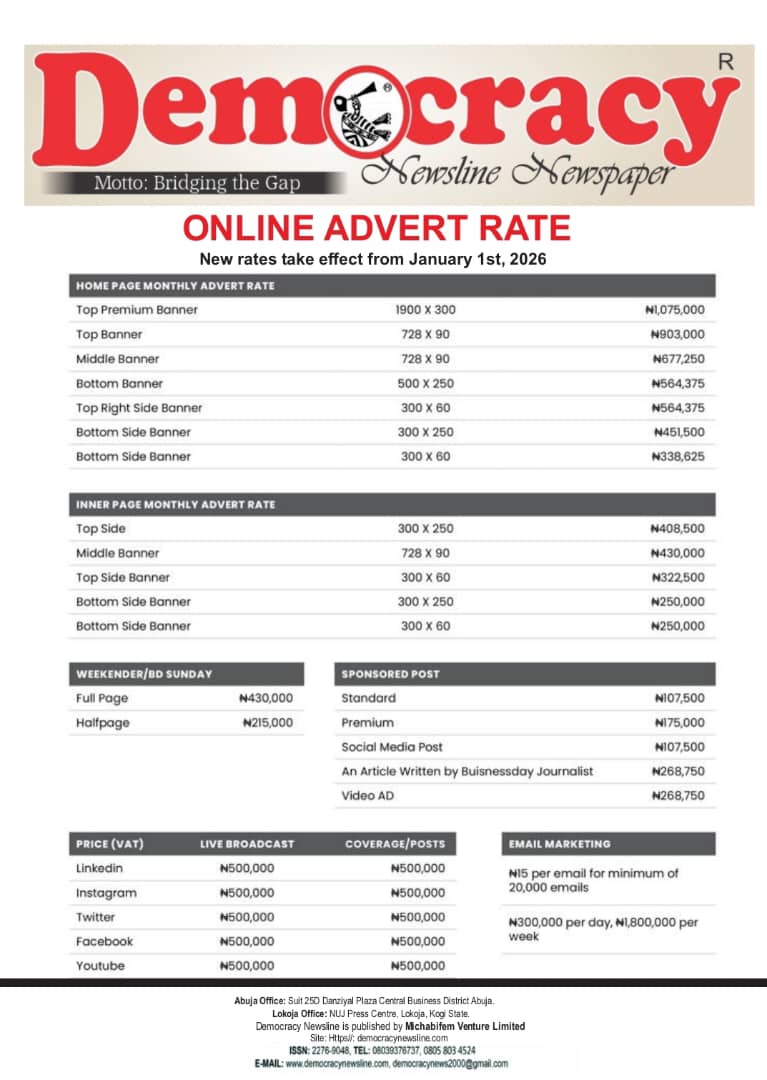

Democracy Newsline

January 29, 2026.

The political temperature in Kano State rose sharply on Thursday as the Commissioner for Information and Internal Affairs, Ibrahim Waiya, publicly urged the Deputy Governor, Aminu Gwarzo, to resign his position following his refusal to align with Governor Abba Kabir Yusuf in defecting to the All Progressives Congress (APC).

Speaking to journalists in Kano, Waiya emphasized that governance at the highest level demands absolute trust, loyalty, and shared political vision, noting that the absence of these values within the executive arm weakens decision-making and threatens stability.

“You cannot sit in sensitive executive meetings when your political loyalty lies elsewhere,” Waiya said. “Government is not a social club; it is built on confidence and common purpose.”

At the center of the unfolding drama is the Deputy Governor’s unwavering loyalty to Engr. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, the national leader of the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP) and the political mentor who midwifed the current Kano administration.

Sources close to the Deputy Governor say Aminu Gwarzo views his mandate as a trust from Kwankwaso and the NNPP political movement, popularly known as Kwankwasiyya, rather than from shifting political alliances.

For Gwarzo, abandoning Kwankwaso would mean betraying the ideology, structure, and supporters that brought him to power.

This loyalty has earned him admiration among NNPP loyalists but has also placed him on a collision course with the governor’s new political direction.

Under the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended), the resignation of a Deputy Governor is entirely voluntary. Section 306(2) of the Constitution clearly states, that; A Deputy Governor may resign by submitting a written notice of resignation to the Speaker of the State House of Assembly.

The resignation takes effect immediately once the Speaker receives the letter.

This means, No commissioner, governor, or party official can legally force the Deputy Governor to resign.

In essence, unless Aminu Gwarzo chooses to step down on his own, the Constitution protects his right to remain in office.

While political pressure mounts, impeachment remains the only constitutional mechanism for removing a Deputy Governor against his will—but it is neither simple nor quick.

Section 188 of the Constitution outlines a strict impeachment process:

One-third of House members must sign a notice of allegations. The notice must detail gross misconduct, not political disagreement. The Speaker must serve the notice on the Deputy Governor. A two-thirds majority of the House must vote to investigate.

The Deputy Governor has the right to defend himself.

Only if the panel finds him guilty, and two-thirds of the House adopt the report, can impeachment succeed.

Defection or political loyalty to another leader does not automatically qualify as “gross misconduct.” Any impeachment attempt based solely on party disagreement may collapse in court.

Waiya maintained that beyond legality, the issue is about governance ethics, insisting that a divided executive sends the wrong signal to investors, civil servants, and the public.

However, supporters of the Deputy Governor counter that the Constitution did not create the office of Deputy Governor as a party enforcer, but as an elected official with a fixed tenure.

Political loyalty versus constitutional rights

Party supremacy versus democratic institutions

Personal conviction versus executive unity

Whether Aminu Gwarzo chooses resignation out of loyalty to Kwankwaso, survives political pressure, or faces an impeachment battle, one fact remains clear: the Constitution, not politics, will have the final word. And in Kano’s charged political landscape, that word may shape the future of power far beyond this moment.

(DEMOCRACY NEWSLINE NEWSPAPER, JANUARY 29TH 2026)